In China, the world's manufacturing powerhouse, a new industry is taking shape: the mass production of mutant mice.

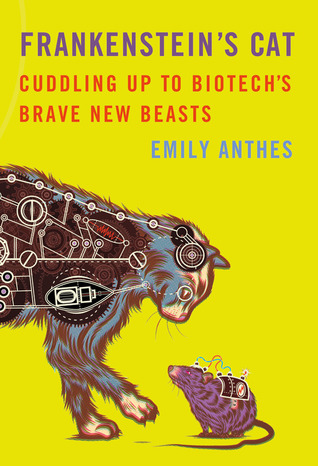

In China, the world's manufacturing powerhouse, a new industry is taking shape: the mass production of mutant mice."For centuries, we’ve toyed with our creature companions, breeding dogs that herd and hunt, housecats that look like tigers, and teacup pigs that fit snugly in our handbags. But what happens when we take animal alteration a step further, engineering a cat that glows green under ultraviolet light or cloning the beloved family Labrador? Science has given us a whole new toolbox for tinkering with life. How are we using it? In Frankenstein’s Cat, the journalist Emily Anthes takes us from petri dish to pet store as she explores how biotechnology is shaping the future of our furry and feathered friends. As she ventures from bucolic barnyards to a “frozen zoo” where scientists are storing DNA from the planet’s most exotic creatures, she discovers how we can use cloning to protect endangered species, craft prosthetics to save injured animals, and employ genetic engineering to supply farms with disease-resistant livestock. Along the way, we meet some of the animals that are ushering in this astonishing age of enhancement, including sensor-wearing seals, cyborg beetles, a bionic bulldog, and the world’s first cloned cat. Through her encounters with scientists, conservationists, ethicists, and entrepreneurs, Anthes reveals that while some of our interventions may be trivial (behold: the GloFish), others could improve the lives of many species—including our own. So what does biotechnology really mean for the world’s wild things? And what do our brave new beasts tell us about ourselves?"

There were many fascinating aspects to this book; the subject is so, so interesting, and the book could have been an intriguing and absorbing look at various new techniques for altering and creating animals. Instead, I was annoyed by the author's writing and use of tacky language, as well as by her heavily, heavily biased slant (more on all of this later).

What Anthes is writing about should be astonishing to anyone; the very idea that humans would be able to say control animals' movements through their brains is such a new one. This is just one of the many mindblowing technologies covered in Frankenstein's Cat, and I certainly enjoyed reading about them. For that alone, this book would get a good rating. But even though the author has a master's degree in science writing, she doesn't know how to write well. Her diction is simply cringe worthy, and I winced many times as I read the book. She uses words like "critters" and "pooches" and at one point talks about using eggs from "plain ol' tabbies". The only reason I finished the book was because what she was writing about interested me immensely. If I had been any less interested, I would have put it down after a few chapters. As it was, I learned a lot, but the experience wasn't exactly enjoyable. The mediocrity of the writing got harder and harder to ignore as the book progressed; perhaps that kind of folksy writing is to some people's taste, but it certainly isn't to mine, especially in a science book. That's not to say that science writing can't use humor to great effect, but this wasn't humor; I don't even know what it was. Perhaps Anthes speaks like this, or perhaps she was trying to interest readers.

The author also churns out painful similes in another attempt to relate to readers. Or something. I don't even know. I also found at least a few portions of the book that seemed somewhat inaccurate to me; at the very least, these passages were vague and misleading. For example: "Consider the enormous variation among human beings, all the different traits possessed by the people in your family, or in your state, or in Mozambique, Sri Lanka, and Iceland." I'm probably just being nitpicky, but despite our physical differences in fact there's not actually a whole lot of genetic variation among humans due to the fact that we all originate from a small original band of Homo sapiens. I get the point she was trying to make (if a lot of individuals of a species are wiped out, there's less genetic variation), but the whole comparison just fell apart for me. Also, she goes on to imagine that only you and the people on your block survive a meteor hitting the earth. But in fact there might be comparatively large genetic diversity on your block (especially if you have the good fortune to live in a city like New York).

And my last criticism: the author's heavy, heavy bias. Inevitably the author's opinion is always a part of a book, but in this case her constant cutting in to talk about her own opinions annoyed me. That actually happens in many science books (in fact many science books are written to persuade people of things), but with such complicated issues, scientific and ethical, at the heart of this book, I couldn't help wondering if there were negative aspects of bioengineering that Anthes was leaving out.

Something about the whole tone of the book set my teeth on edge. I don't understand the recognition it's received or how the serious science community (like Science magazine) can endorse this book. The topic's fascinating, and I suppose Anthes is pretty comprehensive, but the writing to me was atrocious. I wouldn't recommend this one at all unless you're a fan of corny language. It's a shame; the book could have been really intriguing and enjoyable.

181 pages.

Rating: **

No comments:

Post a Comment